|

1950 - Parachuting for fun.

During 1949, Bickertons Aerodromes Ltd (BAL) had applied for permission to extend the back of Hangar J. The two hangars were of different depths and had been reconstructed with their front walls aligned. The application to extend Hangar J by 15 feet was intended to bring the back walls into line. This had initially been refused for an unknown reason, so BAL appealled, permission being granted on 22 March 1950. This meant the back of the hangar could be built and the hangar put into its proper use.

|

The airfield photographed in June 1950, the two hangars evident on the north side would soon be of the same depth.

|

In January it was decided that Denham Air Services, the company that ran the Denham Aero Club should leave. Problems with fuel coupons, as rationing was still in force in the UK, missing fuel and poor accounting all came to a head that month. By February a new organisation, the Denham Flying Club, was founded and took over flying training. Two of the personnel from the earlier organisation, director J. Milli and chief flying instructor Derek Wright remained as part of the new club which began operating in early March. Derek was a very experienced pilot, having flown a wide variety of RAF aircraft during the war, including the Bristol Blenheim and Douglas Boston, before becoming an instructor. The other two directors of the club were M Dickenson and Joan Crane. Joan was a British European Airways stewardess who had joined the company in 1946. She was already experienced aircrew after serving as a nursing orderly in air ambulances with the Women's Auxiliary Air Force during the Second World War. Interestingly, Joan was actually in Berlin with her unit on the day peace was declared to end the war in Europe. She was to stay with BEA, later British Airways, until 1981, celebrating her retirement as their oldest stewardess with a trip on Concorde.

|

Mr Derek Wright, a former RAF instructor, remained as the CFI of the new Denham Flying Club. He is seen here with his secretary, Audrey Warwick.

|

The sport of parachuting, or skydiving as it is often known, was in its infancy in 1950, parachutes having previously been considered solely the domain of the military. Parachutes were initially not adopted by the Air Ministry during the First World War as it was suggested pilots would abandon their aircraft unnecessarily. However, it was realised a parachute gave a pilot a second chance to reach the ground safely if his aeroplane broke up or caught fire, so parachutes were officially adopted from 1923 onwards. By 1950, parachute jumps were still sufficiently rare that the activity quickly drew a crowd, and the jumps at Denham were no exception.

|

Major Willans in classic pose, aboard John Beadle's Tiger Moth over Fairoaks in 1952. Willans at the time was the Chairman of the British Parachute Club.

|

A former military parachutist, Major Terrence Willans, nicknamed Dumbo, began parachuting at Denham and offered instruction in the skills required. He was an old fashioned gentleman, kind, loyal, with an evil sense of humour and a very British embarassment at any kind of praise. He was uniquely qualified to instruct, as he was one of the most experienced parachutists in Europe and was often referred to as "the father of British sport parachuting". His nickname came from an instructor when he was learning to become a paratrooper during the Second World War. On his first jump, he hesitated, and the instructor yelled "Uncurl your ears, Dumbo, and fly!" His early life was hard, Willans was orphaned at the age of 13 in 1931 and emigrated to Australia in 1934, working as a farm labourer and cattle drover, before joining a travelling rodeo show. When the Second World War began, he returned to the UK and tried to join the RAF but failed the colour blindness test. He had chosen the RAF as he was fascinated by engineering and machinery, and had been so from a young age. His grandfather, Peter Willans, had been the inventor of the Willans Steam Engine, a powerful advance over previous engines and his father had been an engineer in York. Willans enlisted in the Army instead, joining the cavalry and training at the Army Equitation School at Weedon and the Officers College at Sandhurst. He then volunteered for parachute training, and on completion became a member of an elite force, the Pathfinders. The Pathfinders were the first troops to be dropped into enemy territory to locate and mark landing and drop zones for glider borne forces and equipment and the parachute infantry that followed behind them. Willans was a young Lieutenant when he first dropped into Italy with his unit, the 21st Independent Parachute Company Pathfinder Platoon. This was followed by him taking part in Operation Dragoon, the invasion of Southern France, before finally being deployed to Greece at the end of the war. His team dropped into Athens at night and fought their way through rebel Communist Elas forces to take the centre of the city and stop the wholesale slaughter of civilians the Communists were conducting against the Greek middle classes. What he witnessed in Athens left him with a loathing of violence that was to last the rest of his life, a life that would be dedicated to saving others.

|

Major Willans during his live trials of the Saab ejection seats for the Folland Gnat.

|

On his return to the UK at the end of the war, Willans was posted to the Army Airborne Transport Development Centre and then to the Airborne Section of the Army Operational Research Group. In both of these postings his engineering interests came to the fore as he was not only researching and developing new parachute equipment but conducting the live testing of the new systems too! Having been promoted to Major by this time, he finally left the Army in 1948 and became a freelance parachute expert. He undertook a number of display drops to raise money for charity, a practice he was to continue for many years. Willans first testing job was for the remarkable inventor and manufacturer Leslie Irvin of the Irving Parachute Company. Irvin and Willans developed and automatic pressure based release system for parachutes to allow the safe recovery of pilots who had lost conciousness at high altitudes or had been injured and were unable to pull a ripcord manually. Willans first live test of the Irving Barometric Parachute Device, as it was known, was from 15,000 feet and was entirely successful. This was followed by a series of tests to advance Irvin's knowledge of high altitude bale-outs and included one jump from 25,000 feet, at the time the longest parachute jump ever made.

|

Major Willans took part in many airshows, including this one at Eaton Bray, where gave a display of wing walking without a parachute or harness.

|

In 1950 Willans began training students in the art of parachuting at Denham and became a competition parachutist, winning the silver medal for Great Britain at the first World Parachuting Championship in Yugoslavia in 1951. Also in that year, he set up Air Advertising Ltd at Denham, in co-operation with the Denham Flying Club. The company arranged aircraft to tow advertising and information banners over any kind of event, the banners being designed to be easily read from the ground and supplied by a number of specialist companies. The new venture became very successful and was quickly noted in the press for their activities at national events around the country. He returned to working for the Irving Parachute Company in 1952 undertaking live tests over the North African desert to research into the prevention of spinning during descent. These tests were so dangerous that no one would insure them and Willans had to sign a waiver that Irving bore no responsibility for his death or injury. These were successful and increased the safety of parachute design enormously. Testing and development did not pay well, so Willans took part in air displays and demonstration jumps between these jobs to earn a living, as well as wing walking without a parachute and other stunts. His pilot at many of these events was Neville Duke, the famous record breaking test pilot. These experiences led him to become a part time film stuntman, appearing as a pirate in the 1951 film Captain Hornblower and later presenting the BBC television programme Summer Magazine.

In 1953 his experience and knowledge of parachuting were recognised when he was elected as President of the Parachuting Commission of the Federation Aeronautique Internationale (FAI). That same year, he began working with GQ Parachutes, a British company researching and designing safer parachuting equipment. While working with GQ, Willans became interested in applying all he knew about parachute harnesses to the design of seat belts for cars, particularly Formula 1 racing cars. GQ began manufacturing his harnesses which sold world wide. In 1954, Willans acted as coach and advisor to the British team for the Second World Parachute Championship in France, a team put together from instructors at the No. 1 Parachute Training School at the request and with the support of Sir Raymond Quilter, the co-founder of the GQ Parachute Company.

|

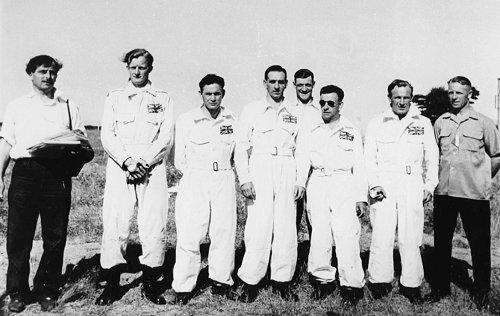

The British team for the Second World Parachute Championship in France, Dumbo Willans, Arthur Harrison, Tommy Moloney, Norman Hoffman, Alf Card, Timber Woods, Doddy Hay and Danny Sutton. Doddy Hay was also to test ejection seats for Martin Baker as recorded in his book "Man in the Hot Seat".

|

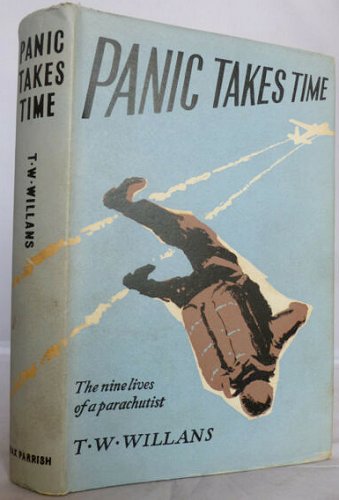

Willans wrote a thoroughly enjoyable autobiography in 1956, wonderfully entitled "Panic Takes Time" and followed this with a childrens adventure story, "The Hangfield Mystery" in 1958. Also in 1956, he began working with Folland Aircraft and conducted the first live tests on the Saab designed ejection seats for the Folland Gnat jet trainer. In 1959 the Royal Aero Club elected him Chairman of the Parachuting Committee, and then voted him onto the Aviation Committee. This was followed in 1960 by the award of the Royal Aero Club's Silver Medal for services to sport parachuting. Willan's 1964 book "Parachuting and Skydiving" is still recognised as a standard text on the subject and continues to sell worldwide. His interest in safety harness design continued until 1968 when GQ stopped car harness production, but Willans, alongside Formula 1 World Champion Jackie Stewart, continued the development privately to improve driver safety in a small workshop in Henley-on-Thames. His quick release system that allowed drivers to escape quickly from dangerous situations was soon to be found fitted to Lotus, Ferrari, Matra, Tyrell and McLaren Formula 1 cars, as well as a host of other application in aircraft and boats, including Donald Campbell's record breaking Bluebird. In March 1972 Willan Harness Manufacturing Ltd was founded and steadily diversified, Willans developing safety harnesses for tree surgeons, offshore oil rig workers and drilling rigs generally. Willans himself was working on the designs in his home workshop in Truro, Cornwall, right up until his death on 10 September 2004. Never a rich man, his work was selflessly dedicated to the safety of others, a remarkable life well lived. The company he founded still exists today, and still develops and manufactures safety equipment and harnesses of many types, a fine legacy for a fine man.

|

Major Willans autobiography is a cracking read if sadly hard to come by, having been out of print for a while.

|

To return to Denham, one of Major Willans' proteges was Britain's first civilian female parachutist, Phyllis Weir, known as Phyl at the aerodrome. Using the aircraft of the Denham Flying Club, Willans, his students and Phyl Weir made many jumps over the aerodrome, an activity that was to continue until 1953. After this point, the London Control Zone was created to provide a safe area around Heathrow airport. The airspace above Denham was dedicated to airline traffic, so parachutists no longer had sufficient height to operate safely. The group moved to Weston On The Green where a parachute club still exists today.

|

Britain's first female parachutist, Phyllis 'Phyl' Weir seen at Denham in 1950 with one of the flying club's Auster aircraft, ready for another jump.

|

The Denham Flying Club quickly established itself, acquiring new aircraft including several Auster variants and a rarity for the time, a nosewheel trainer in the shape of a Piper Tri-Pacer. The clubhouse had been extended to give more room for administration and socialising and do-it-yourself tea was available for visitors.

|

The Denham Flying Club acquired a Piper Tri-Pacer trainer, the nosewheel design being a relative rarity in 1950.

The flying club's shed on the south side of the airfield was exended to provide the new club with improved facilities.

|

The Denham Flying Club settled in and many visitors came to the airfield to watch the parachuting and aircraft. The airfield's usefullness as an asset to the military was about to develop and modern technology was to arrive at Denham, as will be related next.

|

|