|

1940 to 1943 - The early years of the Second World War

In September 1939 with the declaration of war, all civil and private flying was immediately banned. Light aircaft were often placed into storage to await the return of more peaceful times, while many were impressed into service as communications and training aircraft for use by the armed forces. Many of Britain's small civil airfields were closed, some for the duration of the war, but a good number found other uses as the war progressed. Several of the flying club airfields in Kent and Sussex found themselves pressed hurriedly into service as fighter airfields during the Battle of Britain, as the German attacks were concentrated against Fighter Command to begin with and put many RAF stations in the South East out of action for days at a time.

|

In 1940, a German bomb just missed Myles Bickerton's house near Denham Aerodrome.

|

As part of the Luftwaffe attacks against airfields, both Northolt and Denham found themselves targets of night raids, several bombs being dropped in Denham Parish during 1940. One of these missed Myles' house by just a few yards. The miss was extremely lucky for the future of this history! This was not the only event of note at the aerodrome during the war, Denham to was to have a varied and interesting wartime career, fulfilling a number of roles.

|

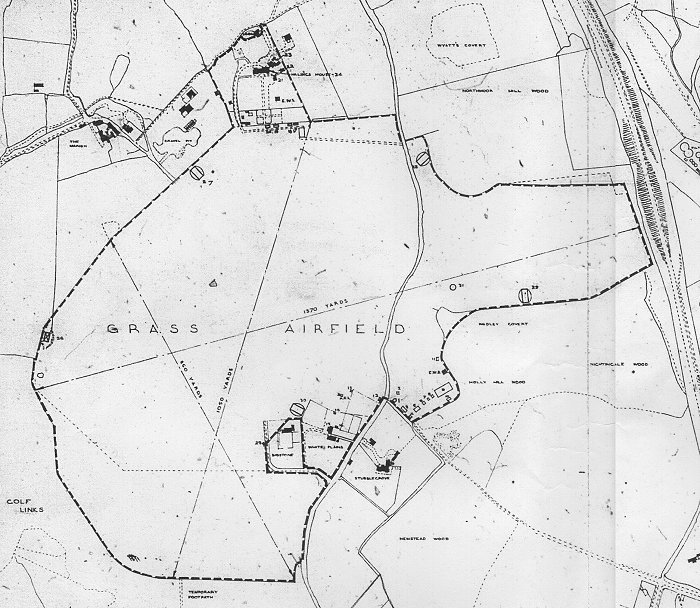

The RAF expanded the airfield in 1941 with the annexation of the field to the East, the closure of Tilehouse Lane, the building of four blister hangars and the annexation of Halings House and its grounds to the North.

|

Denham had, like so many other airfields, been officially closed at the outbreak of war. However, in August 1941 an RAF survey team arrived with a view to re-opening the airfield as a relief landing ground (RLG) to RAF Booker, now Wycombe Air Park. Since June 1941, Booker had been the home to No. 21 Elementary Flying Training School (EFTS), which operated 72 dH.82a Tiger Moths and a smaller number of Miles Magisters, some of which were actually impressed Miles Hawk Trainers, indistinguishable from their military counterparts in their new camouflage paint. The school ran a seven week course for 120 pupil pilots, although as the general war situation improved and the Empire Air Training Scheme began to get up to speed, this initial course was increased to eleven weeks. With that many pupils and aircraft all vying for space in the circuit a second airfield and circuit became vital if the school was to complete its courses on time. Denham was an obvious choice, being close to Booker with well kept surfaces and good drainage, not to mention already containing hangars and fuel facilities. The first actions of the RAF survey team was to recommend the hangars be moved and the centre of the existing airfield be cleared of the trees that surounded them. Next, Tilehouse Lane on the eastern edge of the airfield was to be closed and the land beyond it annexed for the duration of the war, the existing hangars being positioned on the south side of the new extension. All of these changes effectively incorporated all the land from Denham Golf Club house to the Watford Road providing longer landing and take off paths. These changes were made throughout the winter of 1941, but even as the work progressed pupils and instructors began arriving to practice circuits, escaping the congestion at Booker. The first official training flight by a Denham based aircraft took place on 18 November 1941.

|

Duing the war, Malcolm Carlisle worked at Denham as an engineer for Airwork who provided support services to 21 EFTS throughout the conflict. He took this image of the Tiger Moths of F flight at Denham in 1941.

|

The dire need for pilots kept the pressure on the flying training units in the UK into 1942, the situation at Booker remaining hectic despite the use of the Denham circuit. In May 1942 it was decided that F and G Flights of 21 EFTS would permanently move to Denham. Four new "blister" hangars were built to accommodate the aircraft, along with nissen huts for ground crews and instructors. Halings House and its grounds to the north of the airfield were annexed as further accomodation for both the military and civil personnel. Other flights still sent aircraft into the Denham circuit from Booker, but the situation at both airfields was much improved by this move and flying training continued rather more smoothly than had been the case.

|

Many trainee Glider Regiment Pilots began their flying training at Booker and Denham with 21 EFTS. Later, they would go on to fly such heavy gliders as the 8,600 lb Airspeed Horsa.

|

Also in May 1942 a new aviation unit was formed as part of the British Army. This was the Glider Pilot Regiment who would be responsible for taking troop and vehicle carrying gliders into every major airborne operation in the latter half of the war. The gliders were to bring much needed reinforcements, supplies and support equipment in to bolster the otherwise lightly armed parachute forces during such actions as D-Day, Operation Dragoon and Operation Market Garden, as well of course as the final crossing of the Rhine into Germany.

|

One famous use of the Horsa glider was the taking of the vital Pegasus Bridge on D-Day. Troops of the Ox and Bucks Light Infantry under Major Howard were landed within a few hundred yards of their objective, taking and holding the bridge until the Lord Lovat's force from the beaches arrived to relieve them.

|

Many of the pilots of these gliders began their flying training at 21 EFTS, completing a "Glider Course" on Tiger Moths which took 5 weeks and included solo and limited cross country flying. From there the pupils would go to Brize Norton to 21 Heavy Glider Conversion Unit and begin flying Airspeed Hotspur and Horsa gliders. This was followed by an Operational Training course at the same unit, bolstered by a further course at the Operational Refresher Training Unit (ORTU) for 38 Group, which was based at Hampstead Norris. In between these courses, the glider pilots also had to fit in more usual weapons, fieldcraft and other training to make them proficient soldiers as well as pilots. The value of the gliders and the success of their operations is no small testimony to the quality of their pilots. It took a very special breed of man to volunteer to fly an unarmed, unpowered and heavy wooden airframe packed with troops and cargo into drop zones, often at night and under enemy fire.

|

The RP3 consisted of a 60lb warhead, onto which the 3 inch diameter rocket tube was screwed. The rocket was shaped cordite designed to burn consistently.

|

Towards the end of 1942, a weapons development unit began to arrive at Denham, setting up shop in the area around the old hangars on the south side of the expanded aerodrome area. These were a specialist developmental unit of the Instrument, Armament and Defence Flight (I.A.D.F), part of the Royal Aircraft Establishment based at Farnborough. Little is known about the make up of the unit, except they answered to the Government's Chief Scientist, Henry Tizzard and the Assistant Director of Armament Research Ivor Bowen. Like so many other small sub units, they were working on one special project, in this case rocket projectiles. The rocket motors for the standard 3 inch body used in what later became known as the RP3 were mounted on stands on the south side of the airfield and tested for their consistency of thrust and directional stability. According to some sources, occasionally the rockets broke loose from their mounts and shot across the airfield, much to the chagrin of the flying training personnel on the other side.

|

The RP3 rocket projectiles were carried in racks of four and could be fired individually or as here, in salvo.

|

Denham Aerodrome was once again a hive of aviation activity, with various test assets being brought in to the armament workshop and the rapid pace of the flying training being carried out daily. However, more was to happen in the latter stages of the war, as will be described next.

|

|