|

1885 to 1919 - The Beginning

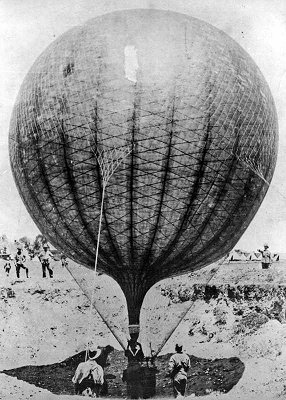

Flying at Denham dates back to the earliest days of aviation. The Royal Engineers (RE) were deployed on exercise in 1885 to survey the area now known as the lakes, which were gravel pits and extend along the side the A412. At least one gas balloon was deployed to assist in the survey. The expanding RE Balloon Section became Britain's first military aviation unit five years later in 1890, deploying to the conflicts in Bechuanaland, Sudan and South Africa.

|

A Royal Engineers observation balloon deployed during the Boer War in South Africa.

|

As interest in the military uses of aviation developed, the Balloon Section became the Air Battalion of the Royal Engineers, taking responsibility for military balloons as well as the first airships and the first heavier than air aeroplanes. The early airships began with the "Nulli Secundus" (Second to None) in 1907, "Baby" in 1909 and "Beta" in 1910. It is believed the modified version of the Beta, the "Beta II", took part in an exercise in the area of Denham in 1913.

|

The Beta II airship is reputed to have taken part in an exercise at Denham.

|

By the time of the latter exercise, the units of the Air Battalion had been subsumed into the newly formed Royal Flying Corps (RFC) which had been founded on 13 April 1912. Once the British Army and Navy and their attendant government bodies, the War Office and the Admiralty, had fully recognised the potential of aircraft for such tasks as reconnaissance and fleet and artillery spotting, then this central organisation was set up to introduce aircraft into service, develop the techniques and equipment required and train personnel. Initially the RFC was to manage the aviation interests of both the Army and the Navy, but on 1 July 1914 the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) was formed to develop naval aviation separately, although the Central Flying School remained a joint enterprise, training flying instructors for both services.

|

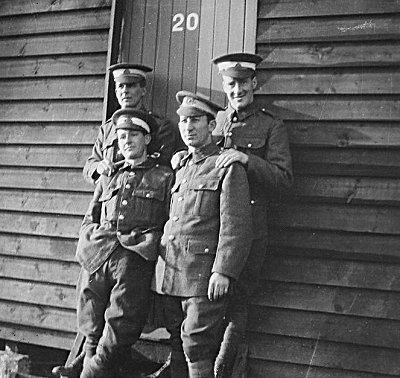

Church Lads Brigade volunteers for 16 Battalion King's Royal Rifle Corps at Moor House Farm.

|

It was in the training role that Denham was to play a major part for the RFC during the First World War, however, the aviation units were not the first to be based in the area. Shortly after the declaration of war on August 4 1914, the first units of the 16th (Service) Battalion (Church Lads Brigade) of the Kings Royal Rifle Corps began to arrive in September. The unit was made up of recruits from the Church Lads Brigade (CLB), founded in 1891 and one of the largest military cadet organisations in the UK up until the 1930s. The then Governor of the CLB, Field Marshall Lord Grenfell, was also an Honorary Colonel of the King’s Royal Rifle Corps, and responded to Lord Kitchener’s appeal for men to join the armed forces by encouraging past and present members of the CLB to join the new Battalion of the Corps. So successful was Grenfell’s appeal that the Battalion boasted over 2,000 applications in a matter of days after the declaration of war. Quickly named “The Churchmen’s Battalion”, men came from all over the UK to join, including 120 from Bolton and 109 from Rochdale.

|

The hutted camp at Denham next to the railway line and Slade Oak Lane.

|

There were so many volunteers that a second Battalion, the 19th, was later formed as a reserve unit. The hutted camp was not complete as the men began to arrive, and so they were billeted in barns and farm buildings at Court and Moor House Farms and Mercer’s Mill amongst others. The St Margaret’s Church parish hall in Uxbridge became a popular venue for the troops where they were entertained and supported by the Church of England Men’s Society who organised games and concerts and supplied magazines and letter writing materials for the visitors. Given the large number of volunteers, early drills were notable for only some of the men having uniforms and everyone using broom handles instead of rifles. Despite this, they were a smart and efficient unit, all of them having been well trained in the cadets for years. Lord Grenfell, The Archbishop of Canterbury and the Battalion’s Commanding Officer, Lieutenant Colonel Kindersley-Porcher, inspected the Battalion when they paraded on Denham Golf Course in early October, by which time the hutted accommodation had been largely completed. The Battalion built an enviable reputation for being well mannered and helpful, and as a result were welcomed in Denham and treated extremely well by the villagers.

|

Lord Grenfell, The Archbishop of Canterbury and Lieutenant Colonel Kindersley-Porcher inspect the Battalion Denham Golf Course.

|

In March 1915, the Battalion left for trench digging training in Rayleigh, Essex, before being sent to Mansfield in Nottinghamshire for Divisional training. After a short spell at Andover, the Battalion embarked for France on 15 November 1915. They were held in reserve during the winter, being ‘seasoned’ with short spells in the front line trenches before they moved up to the front line in the Somme region in July 1916. On 15 July they were in the second wave sent against High Wood. Attacking uphill, in the open, against a dug in enemy with supporting fire from concrete bunkers deep in the woodland, the attack was described by Corporal Jack Beamont of 1 Platoon’s A Company as “a horrible, terrible massacre....” Cpl. Beamont was from Croxley Green and was later to win the Military Medal for his actions. On that day the Battalion suffered 120 casualties, and by September was to lose over half its number with 550 killed or wounded. Throughout the rest of the war the Battalion was to serve with distinction, one of the rare Service Battalions to fight as part of a regular division, later taking part in the bitter fighting on the Ypres Salient in the Spring of 1918, an area they were still deployed in at the war’s end.

|

RFC Cadets of No 1 Officers Cadet Battalion at Denham in 1916. The white band on their caps denotes the fact they have passed the course and are now Flight Cadets.

|

Following the final departure of the 16th Battalion KRRC in April 1915, the hutted camp was soon taken over by units of the Royal Flying Corps which would quickly see the development of the first airfield at Denham. The first to arrive was the 1st Officers Cadet Battalion which was later to become No 1 Cadet Wing of the RFC in June 1916. It is relevant to describe the training system for RFC pilots at this point as it will do much to explain the units based at Denham and their function. Pilot trainee volunteers were first sent to one of several depots, usually the base of a regular Army Regiment, or to the Recruit Training Centre at Halton Camp, before being sent to a Cadet Wing when spaces became available. Here they underwent a two month basic military training course which included physical training and drill, rifle shooting, map reading and navigation, military law and morse code. Aviation related coursework included lectures and demonstrations on airframes and aero engines, their construction and functions. At the end of the course and a physical examination which included balance and coordination tests, the trainees were able to put a white band around their caps which signified they were now Flight Cadets.

|

RFC Cadets have the intricacies of a rotary engine explained in the classroom.

|

From the Cadet Wing, trainees were sent to one of the Schools of Military Aeronautics, which after the formation of the Training Division in August 1917 were steadily renamed Schools of Aeronautics. Over two months the Flight Cadets would learn the theory of flight, compass theory, map reading and aerial navigation. How to rig airframes, that is to adjust the rigging wires of a wood and fabric airframe so the flying surfaces were all square and at the proper angles to one another, was joined by practical aero engine workshops where many different models of engine, both fixed and rotary, were mounted on stands with propellers attached. Cadets were taught to start and run these engines, as well as cure common faults with them. Practical photography with aerial cameras was taught as an introduction to the use of aircraft as reconnaissance platforms. Both the Vickers and Lewis .303in machine guns were studied, fired, stripped, cleaned and reassembled until the cadets could do it in their sleep. The current types of bombs were studied, including instruction in fusing and defusing them as well as the theories of dropping them accurately. Basic aircraft handling skills like taxying, starting up and shutting down were all practiced out on the airfield. Use of the wireless and morse code to assist in the artillery and infantry co-operation roles were taught, and finally the use and workings of flight instruments which completed the course. At the end of these packed eight weeks were a series of examinations which would decide if the cadets passed on to the next phase.

|

Flight Cadets at Denham in 1917 lean against one of the huts that made up the accomodation at the camp.

|

The next phase was flying, with 25 hours of basic handling being taught over three months at one of Training Depot Stations (TDS). Cadets would stay at the same TDS for the second, advanced phase of their training which consisted of 35 hours of cross country and formation flying, reconnaissance and gunnery and at least five hours of experience on advanced, front line aircraft. Finally, the Cadets earned their “Wings” at one of the specialist combat flying schools. These would teach the student air to air combat, bombing, reconnaissance or artillery observation depending on what kind of unit the student was destined for and were of various lengths depending on the subject. By 1918, the process had been streamlined somewhat and the average student went from civilian to combat pilot in around eleven months. The training was dangerous and often took place in a variety of types, some of which were not really suitable as training aircraft. Consequently, by the war’s end, around 8,000 cadets had died in training accidents, in the early stages of the war, before the introduction of the planned training courses, these casualties were around double those being inflicted on the front line in combat. Their average age was 18, and a newly minted Second Lieutenant was paid £5-12s-6d per week, with 12 shillings per day flying pay for every day on which they flew.

|

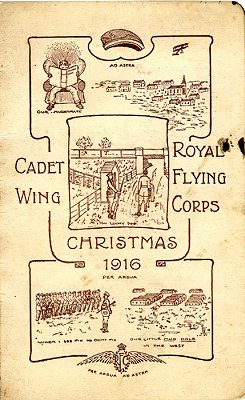

The 1916 Christmas Card from No 1 Cadet Wing at Denham, the last cartoon describing 'our little mud hole in the West'.

|

The 1st Officers Cadet Battalion, later No 1 Cadet Wing of the RFC, was responsible for the first stage of this course, the basic military training with some airframe and engine theory. They moved into Denham Camp in 1915 and expanded the facilities with the addition several large sheds for the instruction of rigging and engine maintenance. Aircraft were initially parked in the open, but two Bessoneau canvas hangars were added in early 1916, followed by two wooden hangars later that year. Types delivered to Denham, mostly by road, included early Avro 504s, BE2cs and ds, dH2s, FE2bs and RE8s, along with a variety of used engines. An airfield was opened up over what is now part of the golf course and the land that Denham Aerodrome occupies today. The first ‘war weary’ airframes were supplied from No 1 Air Depot at St Omer in France and were not supposed to be in flying condition as they were intended for ground instruction only. However, the instructors, several of whom had been front line pilots, with the help of the engineering instructors managed to get a few flying to ‘keep their hands in’, so flying at Denham began in an unofficial way. This changed during late 1916 with the establishment of a training and communications flight which gave some of the cadets their unofficial first flights, kept the unit commanders in touch with other airfields and kept the instructor’s flying skills honed.

|

Used front line aircraft such as this RE.8 were supplied to Denham to become training aids.

|

As the Denham Camp had become a fully fledged airfield by this time, No 1 Cadet Training Wing was moved to St Leonards Camp near Hastings during late August and early September 1917 to continue its basic training work. Replacing it at Denham was a new unit, No 5 School of Military Aeronautics. This had been formed on 1 August 1917 from a cadre of officers and men from No 2 School of Military Aeronautics based at Christchurch College, Oxford and moved into Denham on 8 September.

|

Taxy practice often used wingless fuselages.

|

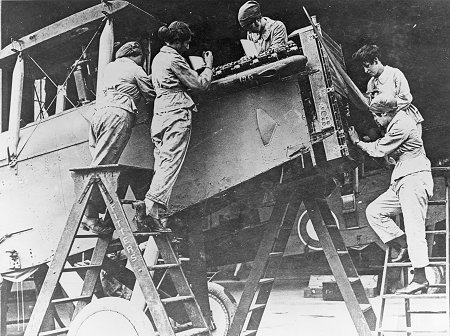

As the war progressed, women took up engineering tasks in the RFC.

|

No 5 School of Military Aeronautics, renamed 5 School of Aeronautics on 1 April 1918, the same day as the Royal Air Force was formed, covered all of the advanced military aviation topics as related earlier. Between 19 August 1917 and 31 March 1918 the commanding officer was Colonel The Lord Alastair Robert Innes-Ker, brother of the 8th Earl of Roxburghe, who afterwards went on to serve in a senior role in the new Air Ministry. As a wooden hut was hardly fitting accommodation, the popular and charismatic officer was billeted in The Marish.

|

Two medical officers of the Womens Royal Air Force outside the later pattern hut that supplemented the earlier Army square huts.

|

Also in command at Denham was Miss M K Fraser, who was in charge of the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps personnel at the airfield, which became a Women’s Royal Air Force Unit after the founding of the RAF. She will re-enter our story in the next installment, but suffice to say that in 1917 she was in charge of the cooks, administrators and serving staff, which gradually grew to include dispatch riders, aircraft fabric and rigging specialists and engineers as women’s roles in the armed forces expanded as the war progressed. No 5 School was to remain at Denham until it was disbanded on 15 February 1919, and was briefly joined by another unit during its tenure. No 6 School of Military Aeronautics was formed from a nucleus of instructors and men from No 5 School on 1 November 1917. It remained at Denham, building up its complement of men and equipment until it was moved to its permanent home at the Elmdale Road Camp in Clifton, Bristol on 23 January 1918.

|

Sir Malcolm Campbell.

|

There were a number of very famous cadets and instructors at Denham during the First World War. Most notable amongst these are two gentlemen who had extraordinary careers in the post war years, the first being the world renowned racing and record breaking driver Sir Malcolm Campbell. Prior to the war, Campbell had been a successful motorcycle and car racing driver, winning the London to Lakes End Trials motorcycle races three times in succession between 1906 and 1908. His attention turned to cars, and his first ‘Blue Bird’ car, a Darracq, was to be seen regularly on the circuit at Brooklands beginning in 1910. Brooklands was also the centre of early British aviation and the new technology caught Malcolm Campbell’s imagination. Aside from the first pioneer manufacturers who had set up workshops, Hilda Hewlett and Gustave Blondeau had opened the first British flying school at Brooklands in 1910, and were quickly followed by schools run by Bristol, Avro, Vickers and Sopwith as extensions of their businesses. Malcolm Campbell, inspired by the pioneer manufacturers, built his own aircraft, the Campbell Briton No 1 monoplane of 1910, similar in design to the Bleriot monoplane that had crossed the English Channel the year before and powered by a two cylinder JAP motorcycle engine.

|

The Campbell Briton No.1 aeroplane at Sidcup in 1910.

|

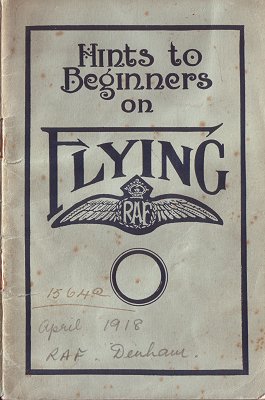

The aircraft was built at Bromley in Kent toward the end of 1909 and taken to field outside Sidcup for flight tests in 1910, where it small engine proved to be insufficient to the task, the aircraft managing only a few short hops. Campbell had spent all of his available resources on the aircraft and was unable to support the venture further, so it was sold at auction to Ernest Maund for £22 10s. Campbell returned to racing at Brooklands and subsequently learned to fly there. With the outbreak of war, Campbell joined the Army as a motorcycle dispatch rider, fighting in the Battle of Mons in August 1914. A commission as 2nd Lieutenant in the 5th Battalion, the Queen’s Own (Royal West Kent Regiment) was promulgated in September, and Lt Campbell found himself quickly transferred to the Royal Flying Corps in the middle of 1915. The RFC were critically short of pilots and his early flying experience made him a rare and valuable commodity at the time. He spent the early years of the war as a ferry pilot, taking aircraft from the various factories and airfields to France, usually the No 1 Aeroplane Depot at St Omer. He became an instructor at Denham’s No 5 School of Aeronautics in November 1917 and while there wrote a book entitled “Hints to Beginners on Flying.”

|

Malcolm Campbell's book was written at Denham in the winter of 1917/18.

|

This was a collection of his personal experiences as a pilot and is genuinely amusing and self deprecating, with its rueful tongue firmly in its cheek. The lessons he had learned were considered sufficiently valuable to trainee pilots that the RAF published the slim 48 page tome in 1918. The book was prefaced by a photograph of Campbell with the Briton No 1 taken at Sidcup in 1910, one of the few images recorded of the aircraft. Discharged from the School in 1919, Malcolm Campbell was to become one of the most famous racing drivers of the 1920’s and 30’s, capturing the World Land Speed Record nine times, and its water equivalent four times in the period up to 1939.

|

Sir Charles Kingsford-Smith.

|

The second famous name associated with Denham is without doubt one of the great pioneer aviators and the first man to fly the Pacific Ocean, Sir Charles Kingsford-Smith. He began his career at 16 as an apprentice engineer with the Colonial Sugar Refining Company, before he enlisted in 1915 into the 1st Australian Imperial Force of the Australian Army. His engineering background meant he was given the task of motorcycle dispatch rider, serving in the ill fated Gallipoli campaign before being despatched to France. The Australian Army was approached by the War Office for volunteers to serve in the Royal Flying Corps, and Kingsford-Smith was one of the first to step forward in September 1916. Having watched military aircraft operating over his position he had become fascinated by aviation and its future, and wrote home telling his family of his plans for his new career path: “My intentions for the future are to take up the game permanently after the war in Australia. There’ll be big possibilities for our services. It is an honourable and interesting career for a young man, as well as a splendidly paid one.” On 16 November 1916 Kingsford-Smith arrived at the 1st Officers Cadet Battalion at Denham where he became a popular but often punished cadet. He was frequently caught leading poaching parties, but when the fruits of such labours were not apprehended he held pheasant roasting parties in his hut, using the open fire to cook the birds. As that winter was one of heavy snow and freezing temperatures, the parties were popular as the hut was the warmest place in the camp. Kingsford-Smith could often be found belting out an unprintable ballad on either guitar or piano or leading gambling schools in various card and dice games. His good looks also made him popular amongst the local girls, and he was frequently punished for being late back to camp. His studies went well, and in January 1917 an instructor was going on a communications flight to Hendon and asked if Kingsford-Smith would like to go along. Consequently, one of the great pioneer pilots made his first ever flight from Denham and was instantly hooked on flying. He wrote home: “We went up to 8,000ft and everything looks like a map. The noise is deafening and the cold intense. I’m impatiently waiting for my own plane now to have some more.” In March, he was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant in the RFC and was, to use his own phrase, “cock-a-hoop”. After the successful completion of his wings course at No 8 Reserve Squadron at Netheravon in Wiltshire, he was posted to 23 Squadron RFC, who at the time were operating SPAD VIIs, a strong and agile French fighter design. In August, he was wounded in combat, his injuries necessitating the amputation of most of his left foot. His recovery took a while, and it wasn’t until March 1918 that he returned to flying duties as an instructor, a position he was to hold until the war’s end.

|

Smithy's Fokker F.VII/3m named Southern Cross about to leave Oakland to begin the first flight across the Pacific Ocean.

|

Kingsford-Smith founded a company with Cyril Maddocks and flew joy rides in war surplus BE.2s and DH.6 trainers in the north of England during the summer of 1919, before returning to Australia in 1921 via a short spell as a barnstormer in the United States. He was already planning the flight he wanted to make across the Pacific when he was granted his Commercial Pilot’s Licence in Australia on 2 June 1921. He worked as a joy ride and air mail pilot in Australia, before becoming one of the first airline pilots in the country when Norman Brearley invited him to fly for the newly formed West Australian Airways. On 31 May 1928, Charles Kingsford-Smith, accompanied by fellow Australian Charles Ulm and two Americans, James Warner, the radio operator and Harry Lyon, the navigator and engineer, took off from Oakland California in a Fokker F.VII/3m he had named Southern Cross. Their first leg was to Hawaii, then on to Fiji, before arriving in Brisbane on 9 June to be greeted as heroes by a crowd of 26,000 people. This first trans-Pacific flight was just one of many record-breaking flights Kingsford-Smith was to make, becoming the first man to fly from Australia to New Zealand as well as making the first eastwards crossing of the Pacific. He was attempting to break the England to Australia speed record when he and his co-pilot, Tommy Pethybridge, disappeared over the Andaman Sea off the coast of Myanmar on 8 November 1935. Despite an intensive search, no trace of their Lockheed Altair, named Lady Southern Cross, was found until an undercarriage leg washed ashore at Aye Island in the Gulf of Martaban eighteen months later. Attempts have been made for many years to locate the crash site, but all without success.

|

The Lockheed Altair named Lady Southern Cross which disappeared over the Andaman Sea.

|

To return to Denham, No 5 School of Aeronautics disbanded on 15 February 1919 and slowly the camp fell into disuse. The golf course was reinstated on some of the land that had been occupied by the airfield and a number of local companies took over several of the buildings, including the large instruction sheds, but many of the accommodation huts were broken up or disposed of. The airfield was still to be used, but more of that in the next instalment.

|

|